Black Higher Education in Tennessee

By Crystal A. deGregory, Ph.D., founder and executive editor of HBCUstory, Inc.

In many ways, education was the greatest and most enduring gift of emancipation. Having been largely denied the opportunity to learn how to read and/or write, Tennessee freedmen bore the vestiges of slavery, including illiteracy. Perhaps because it had been so long denied to them, education was viewed as the natural route to self-improvement and racial advancement. In the spirit of self-determination, they flooded modest freedmen’s schools that were often little more than wooden one-room structures with dirt floors. Sprouting all across the black South, freedmen’s schools were crowded with eager pupils, young and old, some literate, while others longed for their first opportunity to learn.

More than a century and a half removed from the Civil War, the freedmen’s educational legacy persists as freedmen’s schools-turned-colleges. Many of these educational centers are among the 105 institutions that have been federally designated as Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).1 The state of Tennessee bears the distinction of being the home of seven HBCUs: Fisk University (1866), LeMoyne-Owen College (1871) Knoxville College (1875), Meharry Medical College (1876), Lane College (1882), Tennessee State University (1912), and American Baptist College (1924).

Extolling the sacrifices of northern missionaries, most histories of black education in southern cities begin with the arrival of northern missionaries who traveled to the war-torn South to establish education for slaves-turned-freedmen.2 Yet, Nashville has the distinction of a thirty-year tradition of independently owned and operated black schools, which begins in 1833 with the native school (a school founded and operated almost exclusively by literate blacks, whether free or formerly enslaved, for the education of blacks, mostly free, or slaves, prior to the Civil War) of Alphonso M. Sumner, a free black barber. 3

Characterized as “a homeless, friendless, pitiable throng, suffering from cold, hunger, sickness, and death,” there were approximately eight to ten thousand freedmen living in Nashville by 1863.4 While they were eager to learn, most freedmen could not afford even the modest tuition charged by Disciples of Christ preacher Daniel Wadkins’ native school, and other native schools like it. With missionary funding, white Presbyterian minister Joseph G. McKee opened Nashville’s first free colored school on October 11, 1863.5 It spelled the beginning of the end of Nashville’s tradition of education by-and-for black people—a tradition which included original Fisk Jubilee Singer Ella Sheppard Moore; lawyer and businessman James C. Napier; educator and feminist Virginia Walker Broughton and her father, businessman Nelson Walker; businessman and jurist Samuel Lowery; barber and real estate developer James P. Thomas, as well as his nephews John Jr., a surgeon, and James Rapier, who was elected as a Republican to the Forty-third Congress (1873-1875).6

Despite winters with temperatures that reached as low as six degrees below zero and the illness that all-too-often followed in their wake, McKee’s school grew to atleast three hundred pupils in 1865 in the structure he’d erected.7Although it boasted an enrollment of nearly seven hundred students by 1866, McKee’s school could not withstand his declining health, which forced him to resign his posts as alderman, as the county’s superintendent of the mission, and as superintendent of education in 1867. He had fled to the North to regain his health, but it never returned and he died in Ohio on September 25 of the following year after “incessant and almost herculean labors.”8

In December 1866, at a time when “the wildest dreams of colored education did not at first, perhaps, include the university idea,” Wadkins, together with Peter and Samuel Lowery, labored to establish Tennessee Manual Labor University as a college for the freedmen in Nashville.9 Despite being under the auspices of black representatives from the Colored Christian (Disciples of Christ) Church and members of the Colored Agricultural and Mechanical Association, the school, with Peter Lowery as its president, experienced a great deal of difficulty in finding support outside of the black community. When the Disciples of Christ failed to wholeheartedly support the school, the Lowerys received the support of black barber businessman and civic leader Sampson W. Keeble, the first African American to serve in the Tennessee General Assembly. Keeble unsuccessfully tried to secure state funds to support the struggling school in the 1870s, and the school eventually failed, but it is not clear when it exactly closed. While some histories point to 1874, there is at least some evidence of fundraising activity as late as 1881.10

Dedicated on January 9, 1866, the Fisk School (also known as Fisk Free Colored School), which had unofficially begun a month earlier, had northern white missionary support. The namesake of Freedmen’s Bureau commissioner and Union Army Brigadier General Clinton B. Fisk, it was also supported by the Western Freedmen’s Aid Commission (WFAC) and the American Missionary Association (AMA). Despite being incorporated as Fisk University the following year, it had no actual advanced curriculum until 1871 and did not produce its first class of truly college graduates until 1875.11

The same year, the temporary wooden structures that housed Fisk University were rotting extensively. There were insufficient funds for repairs. There was not even enough money for food to feed the 400 students enrolled at the school. Fisk treasurer and music teacher George L. White organized a group of students to sing to raise money to save Fisk. The group’s repertoire primarily consisted of contemporary numbers and abolitionist hymns; yet, when left to their own devices, the students chose to sing the songs born of the slave experience--songs now known as “Negro Spirituals.” The troupe of nine students—which included Ella Sheppard—departed Nashville on a train bound for Cincinnati, Ohio, on October 6, 1871, to save Fisk University.12

Soon named “Jubilee Singers,” because of the biblical reference to the Jewish year of Jubilee in the Book of Leviticus (25:8-17), the troupe had raised $20,000 by the close of its first tour. The funds were not only enough to pay off many of the university’s debts, but also to secure the purchase of the present site of Fisk University.13 The following year, a reconstituted group began a European tour that raised $50,000, which was used to build Jubilee Hall on the new campus. Named in their patrons’ honor, the Victorian-Gothic six-story structure was the first permanent structure erected in the South for the purpose of black education.14

Just five months after Fisk University’s incorporation, Central Tennessee Methodist Episcopal College was incorporated by the Tennessee General Assembly “for the general and theological education of colored people.”15 As the forerunner to Meharry Medical College, the college was transformed under the headship of the Reverend John Braden, who was elected as the college’s first president in 1869. To build a medical department, Braden secured the help of George W. Hubbard, a medical student at Vanderbilt University, and sought the financial backing of the Reverend Alexander Meharry. In concert with his brothers Jesse, Samuel, and David, Alexander Meharry had his brother Hugh convey a tract of farm land valued at $10,000 to trustees of Central Tennessee. Samuel Meharry, who had been deeply moved by the kindness of a black family in his youth, gave an additional gift of $500 in 1875. Together, the gifts made the medical department’s 1876 founding possible. By 1890, the school had produced more than 100 black physicians who served as “more than one-half of the educated black physicians in the Southern States.”16

As “black Nashville’s only comprehensive university,” Central Tennessee and Meharry was not only at the vanguard of providing medical and dental training, other program offerings included a nurses’ course (1878), industrial education (1885), a law program (1882) and a School of Pharmacy (1889).17 Renamed Walden University in honor of Methodist Episcopal Church Bishop John Morgan Walden in 1900, Central Tennessee University’s twentieth-century history was sadly, particularly tragic.18 A December 1903 fire in Rust Hall, Walden’s women’s dormitory, was the first in a series of fires that would signal the end of the school’s forty-year history. Meharry took out its own charter in 1915 and moved to its present location. Renamed a college in 1922, Walden served as a normal and preparatory school until its closure in 1929.

Founded in 1882 under the auspices of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, Lane College opened in Jackson, Tennessee as the C.M.E. High School. Named after Bishop Isaac Lane, who presided over the church’s Tennessee Conference, the school opened with Lane’s daughter Jennie E. Lane as its first teacher. Two years later, the school was formally chartered in Tennessee, and its name changed to Lane Institute. Growing steadily, its curriculum focused primarily on preacher and teacher training until 1896 when the College Department was organized and the Board of Trustees voted to change the name from Lane Institute to Lane College. The successful construction of the college’s Administration Building in 1903 was followed by the thirty-seven-year presidency of Dr. James Franklin Lane, the son of founder Isaac Lane. In addition to improving facilities and the physical plant, the younger Lane attracted the attention of several philanthropic agencies.19

Even so, almost half a century after Fisk’s founding, Tennessee had yet to build a single public center for black higher education. While the Morrill Act of 1862 authorized the establishment of colleges in the new western states and the Tennessee General Assembly’s 1869 guidelines for the land-grant college funding prohibited racial discrimination, the University of Tennessee in Knoxville denied admission to its first black applicants. Black dissatisfaction led the newly elected black legislators to work out an agreement that allowed the state to pay to send the black students to Fisk. The agreement, however, was short-lived, and in its place emerged an agreement with the local Knoxville College, a black school founded in 1875 by the Board of Freedmen's Mission of the United Presbyterian Church.20

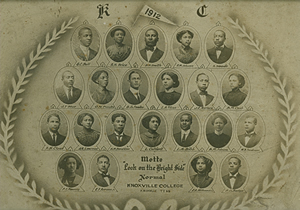

Founded as the Knoxville Normal School, Knoxville College was modeled to some extent on the Nashville McKee School, which closed in 1871. Designated a college in 1877 and guided by Dr. John Scouller McCulloch, the school’s first president, Knoxville College offered teacher-training and college-level courses in the classics, science, theology, agriculture, industrial arts and medicine. The college’s first building, constructed in 1876, was named McKee Hall in honor of the Reverend McKee. Subsequent buildings, including Wallace Hall and McMillan Chapel, were built with student labor. The school operated with the financial support of the State of Tennessee for twenty years until 1912, when the Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State Normal School for Negroes was established.21

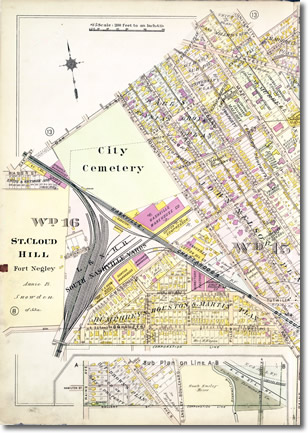

From its perch on 165-acres between Centennial Boulevard and Jefferson Street, what is now Tennessee State University opened its first summer session on June 19,1912. The opening was the culmination of a tireless, three-year effort by the all-black Normal, Agricultural and Mechanical College Association — led by community leaders Ben Carr, Henry Allen Boyd and James Carroll Napier — to have the state’s first and only public center for the higher education of blacks located in Nashville. Guided by its first president, Chattanooga native William J. Hale, and a faculty composed of graduates from many of the nation’s leading liberal-arts colleges, the normal school grew to a college of national repute by 1933.22

A few miles across town, another early African American institution of higher learning would fare less well. The Nashville Normal and Theological Institute had been founded in 1866 by the Reverend Daniel W. Phillips, a white abolitionist. Later financed by the American Baptist Home Mission Society (ABHMS), the Institute changed its name to Roger Williams University in 1883. Although it was located next to Vanderbilt University, the pressures of white streetcar development, as well as devastation by fire challenged its existence. On January 24, 1905, a fire destroyed Centennial Hall. After successfully fighting to reopen, the school was struck by another fire of unknown origin, which leveled Mansion House on May 22,1905. The ABHMS closed the school and withdrew its support, selling twenty-five acres of the Roger Williams campus along with its buildings to the George Peabody College. In November 1910, the ABHMS sold the remaining acreage to white real estate developers, who established a segregated residential subdivision. The final blow to the viability of the school was struck with the National Baptist Convention’s 1915 split into the National Baptist Convention of America, and the National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., both of which began fundraising for their own black seminaries. Finally, in December 1928, Roger Williams’ teachers and students moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where they united with the Howe Institute. Howe had been founded in 1888 as the Memphis Baptist and Normal Institute for West Tennessee Baptists. In 1902, the Reverend Dr. Thomas O. Fuller, the pastor of the First Colored Baptist Church in Memphis, assumed leadership of the Howe Bible and Normal Institute. Howe sold its buildings and merged with LeMoyne College in 1937.23

Made possible through a $20,000 gift by philanthropist Francis Julius LeMoyne to the American Missionary Association, the LeMoyne Normal and Commercial School opened in Memphis in 1871. It moved to its present site at 807 Walker Avenue in 1914, rose to junior college status in 1924, and became LeMoyne College ten years later. After absorbing Howe Institute several decades earlier, LeMoyne College merged with S.A. Owen Junior College in 1968.

While the closure of Roger Williams left an educational void in Nashville, the idea for the founding of American Baptist Theological Seminary can be traced to the 1890s. However, the black National Baptist Convention did not secure the support of the white Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) until 1913. Opened on September 14, 1924, as a black preacher-training school, the American Baptist Theological Seminary struggled under the presidencies of William T. Amiger (1924-25) and Sutton E. Griggs (1925-26) but found a permanent home on White’s Creek Pike in 1934.24

As the progenitors of black higher education in Tennessee, both native and freedmen’s schools helped to shape the culture of the seven remaining HBCUs in operation in the state. In the decades between their founding and the 1930s, they were transformed from schools for blacks to black schools. In doing so, they functioned not only as educational centers but also served -- and continue to serve -- as social change agents and cultural preservationists.

Further Reading:

Crystal A. deGregory, “Raising a Nonviolent Army: Four Nashville Black Colleges and the Century-Long Struggle for Civil Rights, 1830s-1930s,” Ph.D. diss., Vanderbilt University, 2011.

Ibid; “Before Black Athens: Black Education in Antebellum Nashville,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly LXIX, no. 3, (Summer 2010): 124-145.

Notes:

1. The Higher Education Act of 1965 requires that, to qualify for this designation, an institution must be accredited by a national or nationally recognized regional accrediting agency, founded before 1964, and founded for the purpose of educating black students.

2. See Joyce Hollyday, On the Heels of Freedom: The American Missionary Association's Bold Campaign to Educate Minds, Open Hearts, and Heal the Soul of a Divided Nation (New York: Crossroad Pub. Co., 2005); William H. Watkins,The White Architects of Black Education: Ideology and Power in America, 1865-1954 (New York: Teachers College Press, 2001); Jacqueline Jones, Soldiers of Light and Love: Northern Teachers and Georgia Blacks, 1865-1873 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980).

3. The term "native school" is credited to John W. Alvord, a Freedmen's Bureau official. See James D. Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,1998) ; Crystal A. deGregory, “Before Black Athens: Black Education in Antebellum Nashville, Tennessee Historical Quarterly (Spring 2010): 124-145.

4. J.W. Wait, “The United Presbyterian Mission among the Freedmen in Nashville,” in Historical Sketch of the Freedmen’s Missions of the United Presbyterian Church, 1862-1904 (Knoxville: Printing Department of Knoxville College, 1904), 1.

5. Ibid; Daniel Wadkins, “Origin and Progress Before Emancipation,” in A History of Colored School of Nashville, Tennessee, ed. G.W. Hubbard (Nashville: Wheeler, Marshall & Bruce, 1874),

6. deGregory, “Before Black Athens,” 138-142.

7. McNeal, “Biographical Sketch of Rev. Joseph G. McKee,” 10; Janet S. Collins, Free at Last, 1898 (Freeport: Books for Libraries Press, 1972),19; Joseph M. Wilson, The Presbyterian Historical Almanac and Annual Remembrancer of the Church for 1865, Volume 7 (Philadelphia: Joseph M. Wilson, 1865), 25; Wait, “The United Presbyterian Mission Among the Freedmen in Nashville,” 3-4.

8. McNeal, “Biographical Sketch of Rev. Joseph G. McKee,” 12.

9. Alphonso A. Hopkins, The Life of Clinton Bowen Fisk (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1888), 112.

10. Ibid.; See Peter Lowery and John W Chanler, eds., “Charter of the Colored Manual Labor School,” in Tennessee Manual Labor University. Incorporated December 10th, A.D. 1866. Instituted for the benefit of indigent colored youths, etc. (Nashville: n.p,, 1867): Lovett, African-American History of Nashville, 147.

11. Ibid.; Dennis K. McDaniel, John Ogden: Abolitionist and Leader in Southern Education, (Independence Square: American Philosophical Society, 1997), 49, McDaniel observed that “it was common throughout the nation, that institutions were called colleges or universities even though they continued for decades to provide a lower-level preparatory school that had nothing to do with its higher education mission.”

12. J.B.T. Marsh, The Story of the Jubilee Singers with Their Songs (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1877), 16; Joe M. Richardson, A History of Fisk University, 1865-1946 (University, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1980), 25-28.

13. Ibid., 30,32; Andrew Ward, Dark Midnight When I Rise: The Story of the Fisk Jubilee Singers (Amistad: New York, 2001), 123.

14. Richardson, A History of Fisk University, 33-35.

15. “Chapter CXV: An Act to Incorporate the Trustees of Central Tennessee Methodist Episcopal College,” Second Session 34th General Assembly 1865-1866 (Nashville: S.C. Mercer, 1866), 301.

16. “Alumni,” Central Tennessee College, Nashville, Tennessee: Meharry Medical, Dental and Pharmaceutical Department Catalogue of 1891-92, Announcement for 1892-93 (Nashville: Marshall & Bruce Stationers and Printers, 1892), 3; See James Summerville, Educating Black Doctors: A History of Meharry Medical College (University,AL: University of Alabama Press, 1983); Frances Meharry, History of the Meharry Family in America (LaFayette: Lafayette Printing Co.,1925), 12-35, 369-371.

17. Summerville, Educating Black Doctors, 28-31; Lovett, African-American History of Nashville, 155.

18. Summerville, Educating Black Doctors, 40; A former teacher and newspaperman, Walden was a lieutenant-colonel in the Civil War and president of the Freedmen’s Aid Society. “[L]ong interested in Negro education,” he was described as “a friend of the Negro, but not aggressively or at all times, wholeheartedly so.” See “A White Bishop,” The Crisis 8, No. 2 (June 1914), 67-68; For additional biographical information see David Hastings Moore. John Morgan Walden: Thirty-fifth bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church (New York: Methodist Book Concern, 1915).

19. Lane College. “History of Lane College.” Accessed March 1, 2014. http://www.lanecollege.edu/lanepage2.asp?id=010002002; See Paul R. Griffin. Black Theology as the Foundation of Three Methodist Colleges: The Education Views and Labors of Daniel Payne, Joseph Price, Isaac Lane (Lantham: University Press of America, 1984).

20. Stanley Folmsbee, Tennessee Establishes a State University: First Years of the University of Tennessee, 1879-1887 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1961), 1, 37.

21. See Robert M. McDill, The Early Education of the Negro in America: With Emphasis on the Work of the McKee School in Tennessee (Ann Harbor: Edward Brothers, 1943); Bobby Lovett, America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A Narrative History, 1837-2009 (Macon: Mercer Press, 2011).

22. See Evelyn P. Fancher,“Tennessee State University (1912 – 1974): A History of an Institution with Implications for the Future,” Ph.D. diss., George Peabody College for Teachers, 1975; See also Samuel Shannon. “Agricultural and Industrial Education at Tennessee State University During the Normal School Phase, 1912-1922: A Case Study,” (PhD. diss., George Peabody College for Teachers, 1974).

23. See Eugene TeSelle, “The Nashville Institute and Roger Williams University: Benevolence, Paternalism, and Black Consciousness, 1867-1910,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 41 (Spring 1982): 360-379.

24. A. M. Townsend, “Some Observations on the History of the American Baptist Theological Seminary (1913-1951).” Southern Baptist Convention Archives, Nashville, Tennessee, Certificate of Incorporation & Historical Papers, Box 3, File 24; Ruth Marie Powell, Lights and Shadows: The Story of the American Baptist Theological Seminary, 1924-64 (N.p.: n.p.,1964).

Suggested Citation

deGregory, Crystal A. "Black Higher Education in Tennessee." Trials and Triumphs: Tennesseans' Search for Citizenship, Community, and Opportunity. Middle Tennessee State University, 2014. Web.