They Took Their Stand . . . With Race in Mind

by Michael T. Bertrand, Associate Professor of History, Tennessee State University

Tennesseans who came of age in the two decades bracketing the turn of the twentieth century belonged to a southern generation whose shadow would darken their state and region well into the 1950s and 1960s. Theirs indeed represented a defining moment, an epoch whose dusky outline later inhabitants would find difficult to escape. For in addressing what superseded all others as the most important issue of the day – that of race -- they reiterated and seemingly etched deeper into stone, intentionally or inadvertently, a general outlook that inordinately valued tradition and scorned innovation. Their significance lay in stopping time, a feat that was ill-fated and tragic. Neither noble nor heroic (although individual instances of courage regularly occurred), they are not to be confused with the triumphant band of brothers that Stephen Ambrose and Tom Brokaw memorialized as the “greatest generation.” Nevertheless, their actions as a distinctive age group left a legacy just as striking. Walking the earth in an era when the likes of Ida B. Wells, E. H. Crump, James Napier, Edward Ward Carmack, Fannie Battle, W. C. Handy, and “Steamboat Tom” Ryman held sway, this not-so-great generation constructed a present that lived in the past so that it could deny the future.

It was a generation that emerged during the “New South Era,” a quarter-of-a-century span that brought Tennessee to the doorstep of World War I. Advocates of this first New South promoted a vision that promised more than they or it could deliver. Melding together the spheres of economics, politics, and race relations into an imperfect dynamic, the period subsequently produced widespread anxiety and frustration. It was a time of unprecedented urban growth, demographic displacement, unruly railroads, economic depression, agricultural discontent, and political dissonance. The inventory of transgressions that transpired during this seminal phase of state and regional history is a long, familiar, and recurring one: the exploitation of human and natural resources; an overdependence on staple agriculture and extractive industries; the structural perpetuation of disparity between those with wealth, status, and power and those without; the installation of limited government friendly to business yet indifferent to the masses; and a colonial-like reliance on outside investment, skilled labor, and administrative expertise.

An underdeveloped area within a rapidly developing nation, Tennessee and the former Confederacy struggled with provincial feelings of inferiority and negative self-image. The two ultimately adopted as recourse a seemingly permanent defensive posture. Modernity, or perhaps more accurately, the transformative implications of modernity, were not always welcome. Yet modern forces, particularly in the form of technology, were not necessarily alien. Isolation from the nation’s mainstream was never absolute. When couched in traditional terms refined by regional and local custom, however, such forces often turned out to be less than revolutionary. Departure and divergence from convention did not come easily. Expectations or hopes for change threatened to rouse latent tensions, mainly along color, class, gender, and generational lines. Absorbed by a symbiotic process that diffused dissent, this generation yielded to distinctive perspectives and practices that daily denied the passage of the past. What had been good enough for parents, grandparents, and various ancestors regularly stoked the status quo.

The tendency toward conservatism, of course, was not a radical departure for a historically agricultural people well versed in fatalism. Reality often existed as a realm they perceived as outside of their control. Accustomed to God’s laws and volatile temperament, the people closest to the land commonly accepted without question his governance, i.e., the existing state of affairs. They likewise placed their faith in what was around them. Family, kin, and blood were the hallmarks of a folk steeped in localism. Custom, neighbors, and the nearby took precedence over novelty, strangers, and the far-away. The ability to connect was paramount. Everyone took comfort in belonging to a place, a concept that referenced people as much as it did locale. This meaning certainly softened its less flattering flipside -- in a hierarchical social structure that emphasized status, patriarchy, and male privilege, everyone knew their place. Overall, it was a rural world and state of mind predisposed and equipped to thwart change and protect power as well as what everyone knew and cherished as familiar. For the generation that came of age in the chaotic 1890s and the first decade of the twentieth century, looking back to such traditions undoubtedly seemed more reassuring and less frightening than any available alternative.

Illiberal inclinations, therefore, were not tied strictly to the issue of race, and in fact customarily transcended racial boundaries. Such inherent conservatism, however, provided a less than ideal setting for racial progress. Ideology and tumultuous events combined to produce an outcome that proved disastrous. White southerners of all ranks conspicuously accentuated their whiteness, either to consolidate their control and authority, or to compensate for their lack of security and societal clout. They necessarily sought to shape black labor and lives to fit their own economic, political, social, and psychological needs. Accordingly, the period beheld the advent of segregation by statute, black disenfranchisement, and an inconceivable rise in violence directed toward black males. While such phenomena undoubtedly represented the culmination of trends that had been evolving for some time, their implementation at this specific juncture occurred with an intensity and ferocity that suggested nothing less than a complete “capitulation to racism.” The rationalization for such surrender, historian Leon Litwack declared, demonstrated that the generation which reached maturity during this era stood apart, if only by degree, from its predecessors: “Whether described by a ‘moderate’ or an ‘extremist,’ by political rhetoric or by popular culture, black people [were] reduced to something less than human" [1].

It cannot be stressed too strongly that the issue of race played a major role in sustaining a conservative ethos that emphasized continuity. The propensity to equate human beings with animals, for instance, easily embedded itself into a culture that until recently had employed a beast-of- burden logic in support of chattel slavery. Slavery, of course, had long before raised a nearly impenetrable veil between black and white natives; emancipation did little to tear away the gauze. The post-Civil War interaction between the two arguably conformed to an arrangement that resembled social theater. Racial etiquette required that everyone, black and white, put on an act that reiterated the unspoken rules of racial hierarchy. More was concealed than was revealed, particularly behind the masks worn by African Americans, whose very survival relied on pretense. Although many whites erroneously assumed that the façade blacks allowed them to see provided full disclosure, rarely did the simulated roles inspire true camaraderie, authentic affability, or mutual understanding. Consequently, despite centuries of working the same land, worshipping the same God, and creating an interracial culture that vitalized working-class life, the region’s black and white natives hardly knew each other.

For their part, whites in the main saw their African American neighbors as inferior, strange, and so very different from themselves. Suspicion, superstition, and stereotype guided their perceptions and interactions, and would continue to do so long into the future, particularly as whites fretted about post-emancipation urban black life. Black communities disconnected from white authority and direction only exacerbated white fears and phobias. Accordingly, the loosening in the 1890s of internal and external constraints, which since the Civil War’s conclusion had held in check the most blatant racist tendencies, opened the floodgates: white southerners, given free rein in an atmosphere where the inferiority of blacks already was assumed, let their imaginations and actions run amok. Apprehensive about a presumably irrepressible generation of African Americans unaffiliated directly with the institution of slavery, they brought to life jane and jim crow, a pair fashioned to restore racial order and ensure that white forever prevailed over black. For at least the span of its proponents’ lives, “forever” lasted a long time. From lynchings to “separate but equal” and grandfather clauses to “All Coons Look Alike to Me,” the message was clear: “The past is never dead. It is not even past” [2].

Race, as it was defined by those who came of age at the turn of the twentieth century, served as the catalyst for erecting fortifications meant to guard against change. The barricades would remain firmly in place for more than fifty years. Perhaps no one understood this better than historian C. Vann Woodward. In two works published within three years of each other in the 1950s, The Strange Career of Jim Crow and “The Search for Southern Identity,” Woodward established the chronological and conceptual parameters by which future Tennesseans would assess the legacy of a generation that took such a hardened stand against any alterations that might threaten its racial arrangements. In the former, in what became his most popular and influential work, Woodward described how racial segregation laws had evolved in response to the changing political, economic, cultural, and racial environment of the 1890s. After having successfully argued that such legislation was not inevitable, Woodward then, in the latter work, asserted that material forces unleashed by the “Bulldozer Revolution” of the 1940s did exactly what the original champions of racial segregation had feared: it transformed the political, economic, and cultural landscape, thus creating conditions that encouraged an upheaval in race relations. Not insignificantly, Woodward’s “bulldozer revolution” also spawned a new generation, one that finally would help lay to rest jane and jim crow [3].

As useful as it is in describing the disruptive agents that arrived at midcentury, Woodward did not intend for his oversized tractor metaphor to steamroll the earlier cultural fissures that paved the way for the transformative World War II era. He certainly would have agreed with historian Lawrence Levine, who defined culture not as “a fixed condition but a process: the product of interaction between the past and the present.” [4] Cultural scholar George Lipsitz, perhaps, provides the best analogy as to how the process worked. In describing an ocean surface wave smashing into the beach, he concedes that like the bulldozer, the oceanic surge does so with tremendous force. All attention focuses on the impact that occurs at that moment. Yet he also contends that the “breaker” had its beginnings long before, thousands of miles out at sea. Lipsitz refers to the distance between the wave’s points of origin and eventual consummation as the “long fetch.” Relatively hidden from view, the fetch represents the ongoing series of events that make the crashing wave possible. In short, such events epitomize the “interaction between the past and the present.” They consist of causes and consequences that function both independently and incrementally. Thus, in addition to setting the stage, the fetch sometimes deserves to stand in the spotlight [5].

Granted this perspective, Tennessee’s cultural history in the first half of the twentieth century is enlightening. Regional and national trends constantly battled for preeminence; older and newer values vied for permanence. The underlying subtext indisputably revolved around race; agrarian rituals and customs provided the necessary back story. Yet despite resistance from many corners, particularly those hoping to preserve the racial status quo, Tennesseans on several fronts in the century’s first fifty years faced challenges that obliged them to adjust and adapt accordingly. Separately, each arguably appeared as a crashing wave; yet in retrospect, together they comprised a long fetch surging toward the shore, building a momentum that would be difficult to contain. Accordingly, those convinced that the “culture wars” began at the dawn of a new millennium may be surprised to learn of the earlier and similar struggles that established the parameters for more recent clashes. From the 1925 “Monkey Trial” in Dayton that set in opposition religion and science, to the seemingly never ending attempts to legislate morality (“cleanup campaigns” prohibiting alcohol, drugs, and prostitution within urban spaces); from the Tennessee General Assembly’s vote to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment in the face of opposition based partly on biblical support for the subordination of women, to the birth of Piggly Wiggly in Memphis that forced grocery shoppers to choose between community and convenience, modernity and tradition staked the claims over which disciples of each are still fighting.

Much like today, the earlier “culture wars” narrative offered fairly revolutionary initiatives followed closely by relatively reactionary responses. Consider, for instance, the repercussions associated with the 1920s popularity of jazz. Chattanooga native Bessie Smith, who first recorded commercially in 1923, symbolized the power of popular music to flip the conventional racial script, to place white supremacy on the defensive. The favorable reception of jazz by black and white audiences trumpeted the onset of an urban and modern sensibility tied to African American cultural dominance. The rise at the same time of radio barn dance programs such as WSM’s “Grand Ole Opry” in Nashville, however, served to counter the jazz cadence and consciousness of modern life. With its emphasis on “old familiar tunes” and rustic iconography, the point was to frame the Tennessee experience as one of tradition. Like the Vanderbilt Agrarians who published I’ll Take My Stand (1930), the Opry showcased nostalgic models of the country while censuring and marginalizing the ostensibly negative influences of the city. In stressing the “whiteness” of the genre (DeFord Bailey and blackface acts, the exceptions that proved the rule), it tried to recapture rural certainties, both real and imagined, already in the process of slipping away.

Unfortunately, not all return trips to what seemed a vanishing rural world took such a benign path. An updated version of the Ku Klux Klan, while never gaining in Tennessee as great a foothold as it did in other states, nevertheless competed with ministers, politicians, and other like-minded public guardians in defining and stamping out the social sins that littered the road to modernity. Yet in the end, try as they might, Tennesseans could not turn back the clock. One wonders, however, save for the most die-hard, if resetting the chronometer was ever the goal. Barn dance broadcasts, for instance, relied on a technological innovation that brought the outside world and all of its iniquities and immoralities into the homes of God-fearing folk. Nevertheless, few, if any, would have been willing to forsake the radio, a wireless invention that provided news, information, entertainment, and companionship. Similarly, natives did not tear up or refuse to use the state highways built in the 1920s, particularly after the roads had forged new commercial opportunities, including that of tourism, an industry paradoxically based on marketing the state as a timeless entity that merged past, present, and future.

Change, when phrased in terms that did not impinge unconditionally upon local customs, particularly those associated with race, seemed adaptable and acceptable. This is best illustrated when examining Tennessee’s relationship to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, arguably the biggest threat, prior to World War II, that confronted the living legacy of the state’s “not-so-great-generation.” Due to the give and take nature of FDR’s politics, however, the federal government’s response to the Great Depression did not directly alter the racial arrangements that had been put in place at the turn of the century. While numerous benefits in the form of relief, jobs, and construction work of various sorts flowed from Washington to the banks of the Cumberland, Mississippi, and Tennessee rivers and beyond, officials administered the programs by way of home rule[s]. Theoretically, at least, the structure and culture of segregation remained intact.

Yet a funny thing happened on the way to economic recovery: semi-controlled chaos and disruption. First, New Deal agricultural policies inadvertently dislocated countless numbers of those habitually tied to a lineage of dependency; displaced sharecroppers became migrants looking for work. In huge numbers they headed for urban areas.

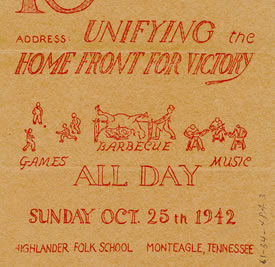

Next, Roosevelt’s alleged support for the collective bargaining rights of every worker encouraged CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) affiliated unions to organize within the state; similarly, Tennessee-born Myles Horton and Don West had founded at Monteagle in 1932 the Highlander Folk School as a center for workshops on labor activism. Suddenly commotion had replaced lethargy. Moving supplanted standing in place. A land so long perceived as inert now generated energy. The symbolism found in the federal government’s sponsorship of the Tennessee Valley Authority could not have been greater; it brought to urbanites, suburbanites, and remaining ruralites alike both electricity and a modern outlook. Thus even before World War II introduced the state to war industries, training camps, military bases, and the material windfall they produced, a sense of optimism rarely experienced within its borders had taken root.

Without doubt, the Bulldozer Revolution transformed Tennessee’s political, economic, and cultural landscape. It was the surge that smashed against the foundations first erected at the turn of the twentieth century. The ebb or receding tide that resulted would wash away many of the vestiges of the past. Remnants would remain, but the new generation that arose from the shore looked with confidence toward the future. The world it aspired to create would not come easy; the journey to get there would be hindered and impeded by obstacles that most could not have foreseen or imagined. The task would be difficult, dangerous, and frightening. Yet unlike its predecessor that came of age in the 1890s, this generation built a world based on hope, not fear. It could do so, of course, because of the momentum that had been generated by the long fetch.

Endnotes

1. “Capitulation to racism” is in reference to the title of chapter three in C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955). For the longer quotation, see Leon Litwack, Trouble in Mind: : Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Knopf, Inc., 1998), 246.

2. “All Coons Look Alike to Me” is a reference to the 1896 song penned by Ernest Hogan. The quotation ending the paragraph is from William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun (New York: Random House, 1951), 73.

3. Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow; C. Vann Woodward, “The Search for Southern Identity,” in The Burden of Southern History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993, 3rd ed.), 6, 10.

4. Lawrence Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977),

5. George Lipsitz, Footsteps in the Dark: The Hidden Histories of Popular Music (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2007), vii-viii.

Suggested Citation

Bertrand, Michael T. "They Took Their Stand...With Race in Mind: Tennesseans and the Issue of Change." Trials and Triumphs: Tennesseans' Search for Citizenship, Community, and Opportunity. Middle Tennessee State University, 2014. Web.