Government & Military

At the close of the American Civil War, the “Reconstruction” of the rebellious former states included federal troops who stayed in place to enforce federal laws, keep order, protect the citizenry and assist with post-War economic recovery. The transition to self-governance came quickly in Tennessee as Governor William Brownlow, a staunch supporter of the Union, convened a new General Assembly. With former Confederate sympathizers barred from voting or holding office, he urged the adoption of an interim constitution to include the federal mandates of citizenship rights for all Tennesseans regardless of race and re-affirm Tennessee’s allegiance to the Union. Thus Tennessee became one of the first former Confederate states readmitted to the United States of America. The subsequent departure of federal armies, which included the mustering out of troops from federal military installations in 1866, was abrupt. Thousands of former United States Colored Troops were left to start their lives anew, with few resources and little community support.

Federal government assistance continued in the form of Freedmen’s Bureau offices in the larger cities and several other locations around the state. The Bureau, which included former federal officers, negotiated labor contracts for freedmen, intervened in some instances during the return of confiscated lands to former confederates, and helped affiliated Missionary Societies and other civilian aid groups found educational institutions such as Fisk University, Central Tennessee College, and LeMoyne College.

Much of Tennessee had been under federal military jurisdiction during the war. Even though most Tennesseans suffered from the scarcity of goods, loss of livelihood, and worse, the military presence did bring with it some commercial activity that boosted the economy.

So also did Tennessee profit during World War I. Farmers supplied United States allies during the early years, selling food and furnishing mules to the British Army for military use. Tennessee’s Mt. Pleasant phosphate proved valuable for munitions manufacturing. The United States Army Signal Corps established an aviation training camp at Millington in 1917. The United States worked with the DuPont Chemical Company to open a military munitions “powder” plant in Old Hickory in 1918. The plant was repurposed in the 1920s by DuPont to manufacture rayon, a newly developed synthetic fabric.

The creation of Tennessee Valley Authority was in many ways precipitated by war efforts. The World War I era Wilson Dam at Muscle Shoals resulted from a federal push for hydroelectric power to supply a military munitions plant. Converting wartime manufacturing into a peacetime effort to supply fertilizer (phosphorous being a prime soil nutrient) for failing farms in the region was cited as one reason for taking control of waterways that could be dammed to control flooding. Most importantly, however, the new federal authority would control electric power production.

Partly as a result of TVA’s growing capability to furnish energy for manufacturing, several locations in East Tennessee would become important production locales for World War II contractors such as Eastman Kodak, one of the suppliers for the secret city of Oak Ridge, and the Aluminum Corporation of America (Alcoa).

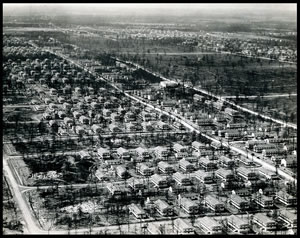

Camp Forrest in Tullahoma, Tennessee, was one of the largest WWII military training bases in the United States. The Army Air Corps pilot training base at Smyrna Army Airfield became Sewart Air Force Base in 1950. The Milan Arsenal, which spans former farmlands in Gibson and Carroll Counties, produced military ordnance under the management of Procter & Gamble during World War II. With a population at least twice the size of nearby Milan and employing thousands of individuals, the plant’s outsize influence can be traced through decades of the social development of the area as it provided one of the first large-scale opportunities for rural African Americans in West Tennessee to find secure employment close to home. Similarly, Montgomery County is home to Fort Campbell, which began as a sprawling World War II U.S. Army training base on acreage that was once farmland along the Kentucky and Tennessee border. Fort Campbell’s economic impact on the surrounding region has been profound. Perhaps nearly as important has been the societal, cultural, and economic impact in Middle Tennessee of military intermarriage and the arrival of refugee populations from war-torn countries.

The widespread impact of other New Deal programs, such as the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Public Works Administration, Works Progress Administration, and the Farm Security Administration, can be found in Tennessee’s built environment today. The FSA/Division of Subsistence Homesteads oversaw the design and execution of the extensive Cumberland Homesteads resettlement project on the Cumberland Plateau; while the CCC provided jobs and job training to support other federal efforts in the state, such as PWA/WPA construction of roads, bridges, school buildings, courthouses and post offices, as well as worker housing near TVA dams under construction; and designing and building trails, shelters, retaining walls, and landscape features for city and state parks, as well as the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Works Progress Administration was responsible for building monuments and restoring historic sites including Nashville’s Fort Negley, a prominent star-design Civil War fortification that had been erected by a labor force of free and formerly enslaved African Americans and Union troops, many of whom were African American enlistees.