Public Education in Tennessee

By Mary S. Hoffschwelle, Ph.D., Professor of History, Middle Tennessee State University

Tennessee's public schools vividly demonstrated citizens' belief in the power of knowledge as a tool of citizenship during the period 1870-1946. While the practice of separation and exclusivity in public education continued for decades, Tennesseans of both races persisted in their efforts to secure public education as an inclusive social right.

Origins

Prior to the Civil War, only white Tennesseans had access to the state's limited and decentralized public school systems. While the 1834 state constitution embraced education as a public good, there was no consensus among white citizens about the value of schools supported by local and state taxes. Some free black children whose families could afford the tuition attended a handful of private schools. Although Tennessee law did not prohibit teaching slaves, few enslaved people had any opportunity to learn to read or write. Consequently, minimal schooling was the norm for most white Tennesseans and black Tennesseans were almost entirely excluded.

The Civil War and Reconstruction brought the first attempts at universal public education in Tennessee. Black Tennesseans founded their own schools and attended those run by the Freedmen’s Bureau, American Missionary Society, and other freedmen’s aid groups. In 1867 the Tennessee General Assembly opened public schools to all children, yet mandated that black and white students could not be taught together. The 1870 state constitution likewise required racial segregation in public education.

Exclusion had become exclusivity, with ambivalent consequences for public education. Without embracing the ideology behind it, black Tennesseans turned segregation to their own purpose: to create positive community institutions that supported their children and developed the leadership potential of black educators. For white Tennesseans, every attempt to improve their own children’s schooling would raise the possibility that black children might receive the same benefits.

1870-1913

Small but critical changes increased access to public schooling for all Tennessee youth between 1880 and 1913. For example, state laws in 1891 and 1899 encouraged counties to offer secondary-level education and open high schools. But racial discrimination exacerbated disparities between the schooling provided to white and black, urban and rural youth. By 1901, historian Cynthia Fleming writes, just over 55 percent of black children were enrolled in school compared to almost 69 percent of white children, up from 44 percent and 58 percent respectively in 1879. Another 1901 state law completed the separation of public education by banning teachers from instructing pupils of a different race. While this cemented the separation of public education by race, it also reflected the reality of African Americans’ successful campaigns to secure black teachers and staffs for their schools. They strongly believed that black educators not only better understood their children’s needs but would serve as mentors and role models for black leadership.

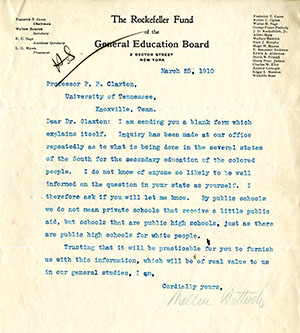

At the turn of the century, black Tennesseans found a new generation of allies in their quest for inclusion in public education: outside philanthropic organizations. A coalition of northern and southern philanthropists and education reformers created the Southern Education Board (SEB) in 1901 to promote more expansive public school systems in states likes Tennessee. Although initially concerned to address the abysmal conditions in black public education, SEB members quickly adapted to the politics of education in the South and focused on improving white schools first.

Tennessee education reformers such as state superintendent Robert Lee Jones, with support from SEB staff at the University of Tennessee like Philander P. Claxton , led biennial campaigns for improvements in public school laws. Their efforts would prove critical to realizing a complete system of public education for whites and a partial one for blacks. The General Education Act of 1909 was their most important achievement. It set aside one quarter of the state’s gross revenue for public education, 61 percent of which would go back to counties on the basis of their scholastic populations. The remainder went to an "equalization" fund to ensure that the length of the school term would be the same in every county regardless of tax revenue actually collected, to county high schools and school libraries, to the University of Tennessee, and to the founding of four "normal schools" focused on teacher training. The normal schools for whites were placed in each of Tennessee's three Grand Divisions; the fourth was a statewide normal school for blacks.

The 1909 legislative provision for state normal schools gave an opening for African American leaders like James C. Napier and Henry Allen Boyd, who secured the fourth state normal school for Nashville. Its title, the Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial Normal School, reflected white preferences for black vocational schooling. More important to African Americans, Tennessee A&I broadened access to higher education. Ultimately, the creation of all four public normal schools improved the quality of elementary and secondary education through the teachers they prepared for the state’s elementary and secondary schools. All evolved into colleges and then universities: Tennessee State University, the University of Memphis, Middle Tennessee State University, and East Tennessee State University.

Without any requirement that school officials allocate state funds equitably, increased support for education did not necessarily mean inclusion in school governance or finances. Local school boards minimized the cost of expanding their educational offerings by redirecting more public funds from black to white schools. Historian Andrew Holt noted that West Tennessee counties with majority black populations found they could use the state’s per-capita funding formula to support new school programs without requiring new local taxes. They simply used the state funds they received for black children to pay for longer terms in white schools.

1913-1930

In the 1910s and 1920s, Tennesseans sought equity within and against Jim Crow for their public schools. Grassroots and professional advocates for public education continued to make common cause with outside agencies that provided financial support and leverage for better schools.

The Rockefeller-funded General Education Board (GEB), created in 1902, became a major contributor to Tennessee’s state department of education and public schools. The GEB paid the salaries of several education department employees. From 1908 until 1925, Tennessee had one GEB-supported “agent” for white rural schools and another for white secondary schools. In 1914 Tennessee added a GEB-sponsored agent responsible for all of the state’s educational programs for African Americans. In keeping with the racial status quo, Tennessee’s “Negro school agent” was a white male educator. Samuel L. Smith was Tennessee’s first agent for black schools, followed by O.H. Bernard in 1920, Dudley Tanner in 1929, and W.E. Turner in 1942. The Julius Rosenwald Fund supplemented the work of the state agent for black schools by paying the salary of an African American educator, who became known as the Rosenwald building agent. One notable example is longtime building agent Robert E. Clay, who worked from the campus of Tennessee A&I, where he was also on the faculty. After 1932, he became a school “developer” for the Tennessee Department of Education.

State staff worked closely with school officials and educators at the local level to expand access and programs in public schools. They also brought in other philanthropic foundations that targeted the needs of African American public schools. All of these initiatives accepted a separate and unequal curriculum for black public schools that emphasized training for manual labor and domestic service. In practice, however, black Tennesseans and their white allies used these programs as leverage for increased spending on black schools and then shifted the focus to improving academics.

The Jeanes Fund offered grants to counties that hired a supervising industrial teacher for rural black schools. Between 1909 and 1959, 105 African American women and men served as Jeanes supervisors in Tennessee counties. Over time they evolved from vocational supervisors to curriculum and instructional supervisors for black schools. The John F. Slater Fund supported county “training schools,” secondary schools for African Americans that emphasized vocational education. The first to open was the 1916 Fayette County Training School in Somerville. By the 1920s, county training schools were evolving into full-fledged high schools with full academic programs. Julius Rosenwald, the president of Sears, Roebuck and Co., and his philanthropic foundation offered matching grants to build modern schoolhouses for blacks that featured special classrooms for vocational programs. Tennesseans would construct 354 schools, 10 vocational shops, and 9 teachers’ homes by the time the grant program ended in 1932.

Tennesseans could point to many achievements from the alliances they forged between local people, school officials, and outside philanthropies. By 1912, 59.67 percent of school-age black youth attended school, and white school attendance had risen to 73.15 percent. A compulsory education law in 1913 required all children from age eight to fourteen to attend school for a minimum of eighty days a year.

As a result, by 1920 white school attendance had increased to 78.71 percent, and black attendance to 65 percent of school-age children. Yet, as Cynthia Fleming has pointed out, the disparity between enrollments had actually grown. Whereas 9.58 percent more white than black children attended school in 1879, by 1920 that figure had increased to 13.71 percent. Disparities between urban and rural schools remained a major problem, spurring Governor Austin Peay’s 1925 General Education Act, which promised Tennessee children an eight-month school term and offered state equalization funds to counties that could not afford the cost.

Charl Ormond Williams led one of the state’s most aggressive public school campaigns to overcome these problems. Williams succeeded her sister as superintendent of Shelby County schools in 1914. As Sarah Wilkerson Freeman has documented, Williams literally rebuilt much of the county’s public school system by convincing her school board to spend $750,000 on modern buildings across the county. When she left to work for the National Education Association in 1922, white teachers prepared a photo album of their schools as a tribute. African Americans knew that Williams had enthusiastically responded to the Rosenwald building grant program for their schools. Shelby County built more Rosenwald schools than any other county in the state.

The inequalities between rural and urban schools could be startling. Urban Tennesseans, black as well as white, enjoyed more access and more extensive public school programs than their rural counterparts. In 1890 Nashville had not only public elementary schools for black children but also four high schools. Pearl Elementary School had opened in 1883, gained an all-black faculty and staff and secondary grades by 1887, and become a three-year high school in 1898. As enrollment surged, black parents forced the city school board to construct a new building in 1915. A school bond issue of $65,000 constructed a new Pearl High School that offered a full four-year secondary program. That was not equity, as historian Sonya Ramsey has pointed out: $250,000 from the same bond issue financed a new white high school. Still, Pearl students could take laboratory science classes and Latin to prepare them for college.

In rural Fentress County, however, a World War I veteran came to realize that the majority white student population had little or no opportunities for any secondary education. Alvin C. York determined that the next generation would have the academic and vocational education needed for the modern world. York Institute opened in 1929 with state funding, and in the 1930s became the only state-administered high school in Tennessee.

African American education in the Williamson County seat of Franklin was more typical of the state’s separation and exclusivity. Franklin was home to the Ninth District Colored School, which black citizens replaced with Claiborne’s Institute in the late 1880s. Although the historical record is unclear about whether the land was donated by Willis Claiborne or a group called the Langston Association, both point to the donation of school land by African Americans. After a 1907 fire destroyed the Institute, the new school building became the Franklin Colored School. Another new building constructed with a Rosenwald grant in the mid1920s became the Franklin (Williamson County) Training School.

1930-1946

During the Great Depression, the state’s public schools suffered along with her citizens. Devastating losses of income and property values threatened to sweep away financial support for public education at the local and state levels. Economic disaster and New Deal federal programs, immediately followed by the emergency conditions of the Second World War, encouraged Tennesseans to fill the gaps in their public school systems by combining local and state with federal funding.

Careful lobbying of the Tennessee General Assembly to protect public education in the state budget and emergency funding from the Civil Works Administration and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration kept Tennessee schools open in the first dire years of the Great Depression. Beginning in 1935, three important New Deal agencies—the Public Works Administration (PWA), the Works Projects Administration (WPA), and the National Youth Administration (NYA)—temporarily replaced depleted budgets and poured federal dollars into the public education infrastructure.

Tennesseans distributed that money in familiar patterns of separation and exclusivity. Nashville’s Pearl High School, which had once again become overcrowded, received PWA funding in 1936 for a new structure designed by the noted African American architectural firm of McKissack and McKissack. Once again, Pearl’s funding paled by comparison with a white school built with the same PWA appropriation, in this case the East Junior High School. But its luster as a leading educational institution in the city and the state shone brighter.

New Deal agencies and federal funding for the Second World War could not eliminate the inequities in Tennessee’s public schools. For example, the Franklin Training School (FTS) ostensibly served the secondary education needs of all Williamson County African Americans. White students rode school buses to Franklin High School but FTS students walked, boarded with black families in Franklin during the school week, or dropped out of school. In the early 1940s funeral home director Tom Patton recruited black citizens to raise funds that purchased two school buses. Their actions split the community as some parents objected to yet another round of self-taxation. Separation and exclusivity continued to promote an ambivalent combination of pride and protest for black schools.

The Second World War heightened public discussion of the meaning of democracy. State curriculum requirements included discussion of democracy, freedom, and civic responsibility that reinforced black teachers’ traditional lessons and had the potential to raise questions for white teachers and students. White Tennesseans had only to read their newspapers to see democracy in action in teacher salary lawsuits. Although Tennessee had adopted a single salary schedule for public school teachers in 1925, it applied only to elementary schools and depended on local participation in the state’s equalization program. High school salaries remained at the discretion of local school boards. Knoxville and Chattanooga black teachers won salary equalization cases in 1940 and 1941. Nashville teachers were the victors when Pearl faculty member Harold Thomas won his lawsuit for equal pay in 1942 with assistance from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Home front defense efforts generated a new revenue stream for public education that even conservative Tennesseans found almost impossible to resist. Communities across the state ballooned in size and demand for schooling skyrocketed around military installations and defense plants. By May of 1942, the Federal Works Agency (successor to the PWA) had already appropriated over $2 million for new school construction as well as operational costs in “congested” areas around Tennessee defense plants and military sites. In the small city of Milan adjacent to the Wolf Creek Ordnance Plant and Arsenal, federal money paid for two new elementary schools, one new high school, and an addition to another school for whites, as well as a major addition to the Gibson County Training School for blacks.

Incremental steps toward equity were no longer sufficient by the 1940s as a series of legal challenges to segregation and exclusion made their way through state and federal courts. African American Tennesseans challenged their exclusion from the University of Tennessee’s law school in a 1939 lawsuit echoing the 1938 US Supreme Court decision in Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada. These court cases predicted a very different future for all levels of public education. W.E. Turner, the state’s director of black education, posed the critical question in a 1938 conference address. “Isn’t the responsibility of providing equal educational opportunity for all the students in the country one to be taken seriously?” he asked. Over the next two decades African Americans would wage multiple campaigns for equality and inclusion and challenge all Tennesseans to recognize each child’s right to a public school education.

Further Reading:

Anderson, James D. The Education of Blacks in the South, 1865-1935. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

Fleming, Cynthia. “The Development of Black Education in Tennessee, 1865-1920.” PhD diss., Duke University, 1977.

Hoffschwelle, Mary S. Rebuilding the Rural Southern Community: Reformers, Schools, and Homes in Tennessee, 1900-1930. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1998.

Holt, Andrew David. The Struggle for a State System of Public Education in Tennessee, 1903-1936. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University Bureau of Publications, 1938.

Freeman, Sarah Wilkerson. “Charl Ormond Williams: Feminist Politics and Education for Equality.” In Tennessee Women: Their Lives and Times, vol. 1, edited by Sarah Wilkerson Freeman and Beverly Greene Bond, 164-90. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009.

Ramsey, Sonya. Reading, Writing, and Segregation: A Century of Black Women Teachers in Nashville. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Savage, Carter Julian. “Cultural Capital and African American Agency: The Economic Struggle for Effective Education for African Americans in Franklin, Tennessee, 1890-1967.” Journal of African American History 87 (Spring 2002): 206-35.

White, Robert H. Development of the Tennessee State Educational Organization, 1796-1929. Kingsport, TN: Southern Publishers, 1929.

Suggested Citation

Hoffschwelle, Mary S. "Public Education in Tennessee." Trials and Triumphs: Tennesseans' Search for Citizenship, Community, and Opportunity. Middle Tennessee State University, 2014. Web.