Towns, Neighborhoods

Look closely at the arrangement of streets, neighborhoods, businesses, and institutions anywhere in Tennessee and you will find a pattern that began with Emancipation in the 1860s, if not earlier: whites clustered in one part of the town and African Americans huddled in another.

One part of this story is the Civil War. During federal occupation of most towns in Tennessee, escaped African American slaves came to the Union lines for safety, and freedom. Union officers created camps for the escaped slaves that they called “contraband camps,” since, in the legalisms of war, escaped slaves were “contraband property.” Once the Union army left, the camps stayed and often evolved into black neighborhoods. The historic black neighborhood in Grand Junction is at the old campsite. The same is true of Clarksville’s New Providence neighborhood, which exists next to the site of a Civil War fort. Crab Orchard, the Union headquarters during the Battle of Missionary Ridge, remains an African American neighborhood in Chattanooga today.

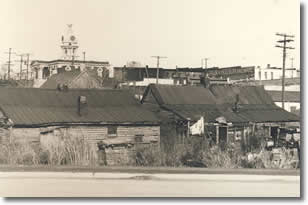

Another part of the story is the impact of the railroad on post-Civil War towns in Tennessee. The old phrase “the other side of tracks” describes a common pattern—African Americans live on one side of the tracks while white neighborhoods exist on the opposite side. Railroads were such an industrial boundary in the late 19th century that they truly defined space, and then race defined that same space in different ways. In Dyersburg, for instance, the railroad’s high grade almost hides the black community from view, but it is there, and at the end of the neighborhood is the landmark Bruce High School building. Trenton is another West Tennessee town where the railroad tracks delineate the boundary between black and white.

The final part of the story is planned residential segregation, long a tool of real estate developers who wished to keep African Americans and other minorities “in their place.” Yet African American developers also designed segregated black neighborhoods. Orange Mound (1880s) is one of the earliest and best known in Memphis. A forgotten one is Hortense, north of Dickson, established in the early 20th century. A church, cemetery, and a few houses are all that remains today.